Troubleshooting Shell Cracking in Investment Casting: Dewaxing vs. Firing Defects

A common challenge in silica sol investment casting is shell cracking after firing, even when no cracks appear after dewaxing. This article analyzes a real case—complete with process parameters and images—to explore potential causes, from shell strength and drying conditions to material refractoriness. Practical solutions are provided to help precision casting manufacturers improve yield and reduce defects.

heweifeng

2/10/20263 min read

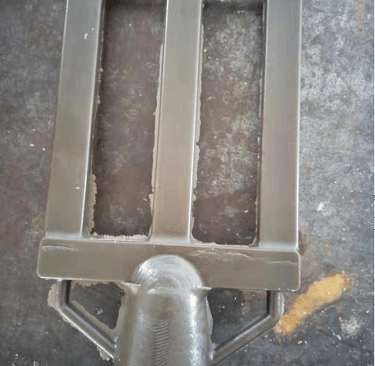

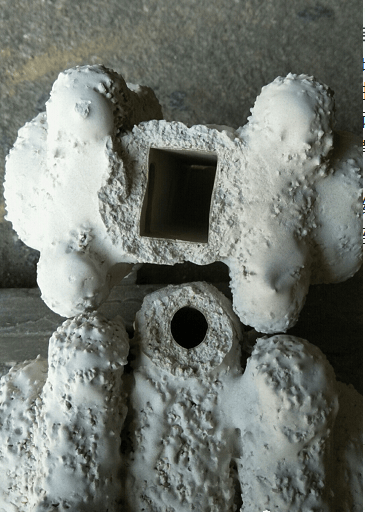

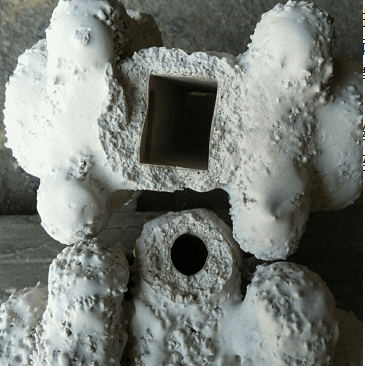

A friend asked me why a particular sprue, regardless of the product assembled, showed no cracks after dewaxing but consistently cracked after firing. Below is a photo of this sprue (Figure 1). Externally, it looks normal—yet after firing, cracks appear. Figure 2 shows one product assembled with this sprue, and Figure 3 shows the cracking after firing.

Figure 1: The problematic sprue

Figure 2: A product assembled with this sprue

(Image placeholder)

Figure 3: Cracks at the bottom of the shell

(Image placeholder)

My friend’s factory uses a silica sol shell-building process. The shell-building room humidity is 48%–54%, temperature is 25°C, and shell firing temperature is 1197°C. The dewaxing autoclave operates at 8 atm and 177°C, with an instantaneous pressure peak of about 6.5 atm and a pressure rise time of around 13 minutes. Shells are built on hanging mobile racks (Figure 4), with one layer applied per day. The result: no visible cracks after dewaxing, but cracks appear after firing—always in the same location, at the bottom cylindrical section of the sprue shown in Figure 1.

Figure 4: Shell drying setup

(Image placeholder)

At first glance, the process seemed fine—except for the 13-minute pressure rise time, which stood out. When I asked for clarification, he explained it was the dewaxing time. So, if the operation seems correct, where does the problem lie?

Generally, shell cracking indicates a strength issue. Shell green strength depends on two factors: shell thickness and drying degree. Thickness relates to slurry viscosity (powder-to-liquid ratio), while drying is influenced by the method and environment (hanging setup, temperature, humidity, airflow). If strength is insufficient (due to thin walls or inadequate drying), cracking would likely occur during dewaxing. Therefore, I suggested starting with a careful inspection of shells after dewaxing.

Unfortunately, my friend found no cracks at that stage. I then asked him to check if the cylindrical part of the sprue was thinner than other areas, which could weaken it. He sent Figure 5, but no obvious thickness variation was visible.

Figure 5: Thickness comparison of the assembly

(Image placeholder)

Normally, firing does not create new cracks—it only expands existing ones—unless handling is rough. I asked if shells were stacked, but he said no. Regarding shell structure, he used face coat–fine–fine–coarse–seal coat layers. Given the firing temperature of 1200°C, I wondered if the refractoriness of the material was insufficient. He mentioned that even with two coarse layers, the same sprue still cracked, which puzzled me.

Based on the above, I believe the cracking may come from two sources:

Microscopic cracks already present after dewaxing, too fine to detect easily. This likely relates to shell drying conditions.

Potential issues with the refractory material’s heat resistance. A 4.5-layer shell fired at 1200°C could easily crack if the material contains impurities or lacks adequate refractoriness. In a previous company, changing raw materials led to shells breaking at 1100°C before pouring (for golf club heads with 0.8 mm wall thickness). This requires further investigation.

Another possible factor is the cylindrical shape at the sprue base. This design differs from typical sprues and might contribute to the problem, though I can’t be certain.

Finally, I advised my friend to:

Apply an extra coarse layer specifically to the cylindrical base before coating.

Replace the round base with a square design to see if it improves.

Quality

Precision manufacturing for diverse industrial applications.

Services

Products

393055590@qq.com

+8615912702921